Why I Think John Malone is Wrong About Roku

Last week, in his annual interview with CNBC anchor David Faber, respected investor and former cable CEO John Malone discussed his perspective on the future of streaming media. In particular, he highlighted the growing power of streaming television hardware / operating systems like Apple TV, Amazon, Google and Roku:

“I think these global platforms will be enormously powerful. And most product creators will be selling wholesale through these transport systems… they will be part of a package or bundle. The consumer is not going to want to buy from a broad number of subscription services, they will want to go to one convenient supplier. It looks increasingly like that will be Amazon, Apple, or Roku, or it could still be Google.”

Given Malone’s experience in the cable industry, I think his perspective is understandable (and of course well informed). To explain why I think he’s wrong about the power of these technology platforms as distributors, it’s helpful to review how the economics of the legacy television industry evolved over time:

1950-2000: Distribution Becomes King*

Over-air television launched in the US in the early 1940s with the “Big Three” networks (ABC, CBS, NBC) offering free ad-supported content to any home within reach of a broadcast tower. Starting in the late 1940s and early 1950s, entrepreneurs began running coaxial cable to small communities around the US, extending the reach of these broadcast networks to viewers outside signal range. This proved profitable, and over the next 20-30 years a web of new cable systems came to cover large parts of the country.

Enter Ted Turner: In the early 1970s Turner created the first cable network, convincing a few wired cable systems in various far-flung locations to offer his Atlanta-based “Superstation,” in addition to the standard broadcast networks (the Turner signal was transmitted to these cable systems via satellite). For the first time, this meant that a viewer could watch a TV network with a signal originating outside their local market (this was facilitated in part by a change in FCC regulations). This proved successful for the cable systems, as it allowed them to offer customers more content and charge higher prices.

At roughly the time Turner was executing his cable network plans, John Malone took over as CEO of TCI, then a modest Denver-based cable system. Through 20 years of successful expansion and acquisition, Malone would ultimately piece together the largest cable system in the country.

In the early days of cable television (late 70s through 90s), content network creators like Ted Turner desperately needed one thing: broad distribution on the wired cable systems. And Malone, as CEO of the largest cable system, was the gatekeeper. How did this play out? New content networks, eager for distribution, would offer favorable economics to TCI (often including material equity stakes) in exchange for carriage on their cable systems.

This distribution environment, which lasted for about 20 years, was great for TCI and Malone:

2000-2015: Revenge of the Networks

Starting in the late 90s, there were two important changes: First, many cable networks achieved wide distribution and viewership, which allowed them to attract a loyal audience and invest in unique, expensive programming like sports. Second, Dish and DirecTV launched satellite pay-TV services, introducing new competition to the network bundling and distribution business thus far dominated by cable systems.

What happened? The leverage between content networks and cable systems flipped. Programming costs (the cost to a distributor of carrying content networks) rose sharply. Content networks with “must have content” like ESPN were able to steadily raise the fees they charge to cable systems over the next 15-20 years.

It’s important to understand the negotiating dynamic here: there were many disputes in the early 2000s where a content network would threaten to pull their programming from a cable or satellite distributor. In nearly all cases, the distributor (e.g. Comcast) would eventually accept large fee increases from the content network (e.g. ESPN), for fear of permanently losing customers. From the customer’s perspective, whether their content networks came through Comcast (the later acquirer of TCI’s assets), DISH or DirecTV was irrelevant, so long as they could watch their ESPN.

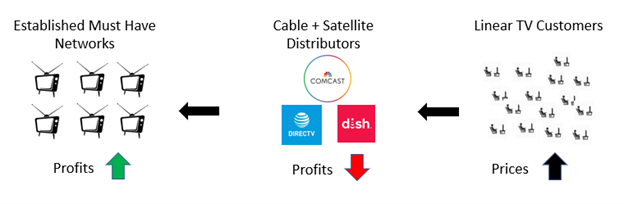

The world from roughly 2000 to 2015 looked more like this:

As a result, video profit margins for cable and satellite distributors have fallen sharply, approaching zero (cable is nevertheless still a great business because of high margin broadband). Content networks, on the other hand, built increasingly profitable businesses over this period, with some achieving 40-50%+ margins at peak in the mid-2010s. Distribution was commoditized and margin flowed to the most powerful suppliers, especially ESPN and regional sports networks, which had unique must-have content locked up in long-term contracts.

A New DTC World

Fast forward to the present day: the US television ecosystem described above has been completely upended by internet based direct to consumer (“DTC”) streaming content offerings like Netflix and Disney+. As a result, linear cable television may well cease to exist within the next 20 years (a much longer discussion, though I believe this is likely).

The current state of play in DTC streaming: Netflix has exploited their first mover status over the past 10 years to build a large global business, with about 200 million subscribers. Amazon followed Netflix a few years later, with Apple, Disney and other legacy media network companies launching their own offerings more recently. Viewership is now steadily shifting from legacy television to DTC, as seen in declining linear ratings and video subscribers. Consumers access all this content through a combination of add-on hardware like Apple TV, Roku, Chromecast and pre-installed software on smart TVs (I refer to these collectively as “tech platforms”).

So how will this new ecosystem play out going forward?

I think there are several important lessons from the history of the cable industry. From Malone’s comments to Faber at the start of this article, he appears to view the tech platforms as the new bundlers and global gatekeepers, akin to the role that TCI itself played in the US in the 1970s-1990s.

There are lots of new direct to consumer streaming media businesses desperate to get their app and content in front of consumers – just as the Discovery Channel was desperate to reach viewers when they first launched in 1985. Unquestionably, some of these new DTC services will (at least initially) be willing to pay a toll to distributors to quickly build scale:

But I think this is a temporary phenomenon, and there are several important factors to consider as it relates to how the new world of streaming will play out over the longer-term:

1) There is no concept of finite hours or primetime programming slots in streaming: the content is by definition “random access.” In the 1980s-90s, niche networks could build a business around special interest content that the prominent early networks like Turner couldn’t, because there were only so many hours in a day for an individual network.

Cable networks began with general entertainment offerings (TBS, TNT, USA) followed by increasingly specialized content (Food Network, HGTV, Travel, etc.) focused on unserved niches. In streaming, the largest platforms can themselves be Food Network, HGTV and Travel Channel, simultaneously. In a sense, the major DTC services are already their own aggregators.

2) This leads to my perspective that DTC streaming content will likely be winner(s) take all. Scale is everything in streaming, in a way that wasn’t possible in the US cable network environment. Not only are content hours unlimited, but a service can be global, with billions of potential customers. Streaming over the internet makes the geographic limitations of local cable franchises and satellite orbits irrelevant.

And DTC streaming is a fixed cost business – producing Game of Thrones costs the same amount to HBO, or a much larger platform like Netflix. The biggest platforms will be able to amortize their content costs over a much larger user base, allowing for lower prices to customers and greater profitability.

In the example below, a new streaming service with 50 million subscribers sells their service at a 33% discount to Netflix, while Netflix spends 4x more on content. Netflix can offer a far better customer value proposition (4x the content for 1.5x the cost) and still operate at an attractive profit margin. The new entrant remains underwater:

A more substantive discussion of breakeven economics for DTC streaming is beyond the scope of this essay, but I think these rough numbers are useful as a framework.

3) As a result of this dynamic, sub-scale DTC platforms simply won’t be able to compete economically. The best content will be purchased by the largest platforms, and a superior brand and price/value equation will drive more efficient customer acquisition economics.

Most of the smaller DTC operators, rather than building out profitable niche platforms as we saw in the cable network world, will simply remain unprofitable. As legacy media companies face greater financial pressures in the coming years, there may be less appetite to subsidize these business ventures.

Conclusions

So, getting back to Malone’s prediction, where does this leave the tech distribution platforms like Roku and Apple TV longer-term?

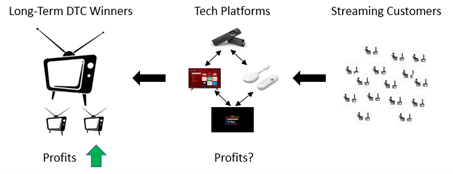

First, these platforms are already somewhat competitive and commoditized, akin to cable distribution after the launch of satellite – and we’ve seen how that played out unfavorably for distributors in the early 2000s. The situation is even worse here though: the supplier base (the “long-term DTC winners” below) will likely be much more concentrated and powerful, and switching costs between tech platforms are lower, given the numerous cheap hardware options and lack of contracts or physical infrastructure involved:

There’s also the possibility that television manufacturers could demand greater economics from these technology platforms (e.g. TCL from Roku), as the pre-installed operating system is an increasingly important driver of which tech platform a consumer uses to access content.

Given these dynamics, it’s hard imagine the tech platforms amassing significant market power and profit margin. It seems more likely that the scaled DTC streaming content platforms, where Netflix has a wide early lead, will extract the most profitability from the system.

One last point – these TV operating systems are in a much different place today than the mobile phone operating systems (Apple and Android). Mobile platforms have seen very high user loyalty and support a huge, fragmented ecosystem of apps that are entirely reliant on the mobile OS for revenue. There would need to be dramatic changes in how users interact with TVs (beyond video entertainment) to approach the dynamics in mobile. In the event this did happen, presumably Apple and Google would be best positioned in TV given their scale and adjacent mobile OS businesses, but that’s a discussion for another day.

Either way, with apologies to John Malone, I’d still bet against a pure play TV tech platform like Roku earning attractive profit margins as an aggregator / distributor in the new streaming DTC world.

Please send any feedback to: anothercynicaloptimist@gmail.com

* This history of the early cable industry is detailed in the excellent book “Cable Cowboy,” by Mark Robichaux (2005)